Each genre, be it in film, television, literature or music, adheres to its own set of rules and conventions. Occasionally these expectations need to be altered or shattered completely in order to keep the genres from becoming stale. Hardboiled fiction and noir are two of those genres whose characterisation is specific, brutal in its crudeness and gritty with darkness and colourful unsentimentality. So when the obscure interpretation of this genre arises, it not only challenges the conventions of noir and hardboiled but in fact reaffirms it to make it even stronger by playing with these conventions. But so rare are the examples of obscure hardboiled fiction that it does not encompass a complete list, though there are a few instances where the conventions of noir are ripped apart and reinterpreted quite nicely, keeping the genre suitably fresh.

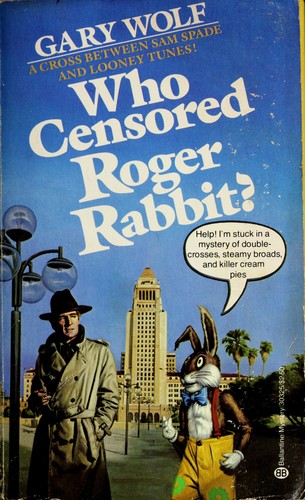

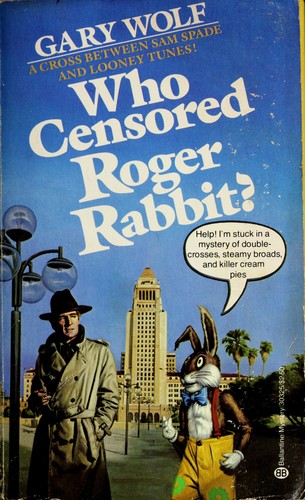

Noted as a children’s classic, but found in the ordinary film section of JB-HI FI, the Steven Spielberg film Who framed Roger Rabbit? (the title possibly inspired by Agatha Christie’s classic Who killed Roger Ackroyd?) is an underappreciated subgenre of the hardboiled detective genre. Based on the little-known book Who Censored Roger Rabbit? (1981) by Gary K. Wolf, , the quirky comedic twist on noir tells the tale of a cartoon rabbit who is framed for murder. After cartoon creator Marvin Acme is seen playing paddy-cake with Roger’s wife Jessica Rabbit—the very epitome of hardboiled femme fatal, with her impossibly perfect hourglass frame, red hair, sultry eyes and velvet voice—he is later found dead. When Roger is targeted as the prime suspect, he enlists the help of reluctant detective-to-the-toons, Eddie Valiant, who uncovers a comic conspiracy. The film became a classic and features the jazzy film score of composer Alan Silvestri, performing with the London Symphony Orchestra. Bob Hoskins’ Eddie Valiant is the disgruntled, world-weary hardboiled detective par excellence, with a suitable hatred of the toons he works for, before glimpses of his personal life and inner self soften his prickly façade. One poignant, noir-driven scene shows Valiant pouring out a bottle of scotch before throwing it up in the air and shooting it with a cartoon bullet.

The book differs quite a bit from the film. Rather than Marvin Acme being at the centre of the murder, Roger Rabbit himself is the one who is murdered. In Wolf’s universe, comic strip characters rather than cartoon characters can converse with humans, with their speech bubbles being visible, and comic strips created by photographing the characters. Also in the book version, conversely to the film, the comic strip characters are able to be killed, though they can create a doppelgänger of themselves that turn to dust after a few minutes. Wolf dedicates the book to Bugs, Donald, Minnie and ‘the rest of the gang at the B Street Smoke Shop.’ Early in the novel Valiant makes a humorous observation about the liquor that toons drink:

Since Toons could not legally buy human-manufactured liquor, most drank the moonshine produced by their country cousins in Dogpatch and Hootin’ Holler. Potent stuff. Few humans could handle it. Although no stranger to strong to drink, I knew my limitations well enough to pass.

Later, Valiant witnessing Baby Herman, a toon whose a 36 year old man in a baby’s body, smoking a Havana cigar: ‘He lit up and exhaled a cloud that would have done credit to a locomotive.’ We then get a great hardboiled reference to one of the masters of the genre, Dashiell Hammett: ‘I cradled my head in my hands. What had I ever done to deserve this? Other detectives get the Maltese Falcon. I get a paranoid rabbit.’

And of course, whether in the film version or the book, Jessica Rabbit (voiced in the film by sultry-voiced Kathleen Turner) embodies the femme fatal to a tee: ‘A knockout. Every line perfection. Creamy skin, a hundred and twenty pounds well distributed on a statuesque frame, stunning red hair. Easily able to pass for human. “What did someone like this ever see in a cartoon rabbit?”’Fans of traditional hardboiled noir will easily be fans of this ode to the genre with a comedic twist. It takes the edge of what might otherwise be a fairly mediocre tail.

South of the border there is Christa Faust’s Hoodtown. Hoodtown is described as a ‘Lucha-noir’ novel. For those wanting a change of location and occupation, this fish-out-of-water noir offers the reader a sumptuous banquet of culture shock, women fighters and a culture obsessed with the act of masking:

‘Now maybe you don’t have hoods in your nice suburban neighbourhood, but this ain’t Cobalt Street, baby. This is Hoodtown. Secreto City. La Yasa. The story takes place around the rather macabre event of Lucha libre wrestling. It follows former luchadora turned private eye ‘X’, who begins to investigate the murders of unmasked prostitutes, the unmasking considered a dishonour. A Marxist would find the work an intriguing statement on class structure in Mexico, considering the discrepancy between the masked and the non-masked. For those noir fans, Faust provides a strong, hardboiled female voice in a genre otherwise occupied by men (although Sara Paretsky and Patricia Highsmith are good contenders). Faust happens to be the first woman published in the prestigious Hard Case Crime series, featuring such notable authors and hardboiled masters as Lawrence Block and Donald E. Westlake.

Described as ‘Casablanca with wrestling masks’, Hoodtown is an innovative addition to the noir oeuvre, and the dialogue is snappy and exudes traditional noir charisma, though undoubtedly brings new scenarios to the table. Those hoping to brush up on their Spanish will also benefit from reading the novel, which provides a glossary of ‘Hoodtown slang’ including the ever popular ‘cajones’, and ‘dinero.’ And, in keeping with the hardboiled noir theme, Faust assures her readers that X is anything but a hero:

Name’s X. I’m a wrestler, at least I used to be. They used to call me the Ice Queen, on account of my ice-coloured eyes and emotionless persona in the ring. I’m a ruda, a stone cold bitch and no kinda hero, but I still have a story that needs telling. Oh, and in case you couldn’t tell by this mask on my head, I’m a hood.

Set in an entirely different culture than traditional noir is used to, the culture clash between the masked and the unmasked (the latter purporting to be superior) makes for an intriguing read.

Jonathan Lethem, an editor of the work Kafka Americana, meshes two cult genres: noir and sci-fi, in his much neglected work Gun, with Occasional Music (1994). Opening with a Raymond Chandler quote, Lethem follows private detective Conrad Metcalf through a futuristic San Francisco, hired by a man accused of killing a urologist. Amidst the dark and dank locations Metcalf bumps into all kinds of strange characters, including one sly kangaroo by the name of Joey Castle who works for the boss of the mafia:

I let Angwine chew that over while I nursed my drink and took a look around. My eyes had grown accustomed to the dim lighting, and I could make out the other patrons of the bar at the far-off tables—but only just. I was a little surprised to see an evolved kangaroo drinking alone near the window, his furry face backlit with moonlight. He was staring at our table and looked away when I glared at him, but there was no way he could hear what we were saying and I wrote it off. The rules barring the evolved were slackening everywhere, and bigots like me were just going to have to get used to it.

Lethem is not without humour though:

Standing in the doorway was the evolved kangaroo I’d seen in the bar of the Vistamont. He was wearing a canvas jacket and plastic pants with a tight elastic waistband, and his paws were tucked into his pockets. He stepped into the room. I got up off the edge of the bed. “You’re in too deep, flathead,” he said. He spoke in a clipped, recitative way, in a voice that was a bit too high to sound as tough as he wanted.

Like Wolf, Lethem blends the ludicrous with the dark, featuring evolved animals that can talk including a kitten and an ape. There are also technologically advanced children known as ‘baby-heads’, who are able to surpass adults in terms of intelligence. Quite dystopian in theme, toward the end of the novel, after Metcalf has been frozen, society deems memory a social taboo, while private investigation becomes illegal. A dark work that fits the mould of noir superbly, readers will find it shares similar traits to the works Brave New World and Blade Runner in terms of bizarre social mores and strange, artificial characters. A cult classic that has been underappreciated in both the science fiction and noir genres, this is a strange albeit arresting novel that would appeal to noir aficionados looking for darkness within the absurd.

There are many strange and alternative noir thrillers, including Rudolph Mate’s 1950 noir flick DOA that sees the protagonist attempting to reveal the identity of his own murderer, leading journalist David Wood to state that the film had one of cinemas most innovative opening sequences of all time. Orson Welles’ 1947 classic Lady from Shanghai was also branded by film critic Dave Kehr as ‘the weirdest great film ever made.’ But in keeping with the sci-fi theme I thought I’d bring up an old favourite. While noted for its mastery of filmic subtlety, the French New Wave movement was not restricted to stories of neglected women, doomed criminals and tragic, philosophical love affairs. In Jean-Luc Godard’s science fiction masterpiece Alphaville: une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution (1965), the director taps into the popular theme of dystopian futures, wherein a characteristically grim and no-nonsense detective Lemmy Caution (a brilliant Eddie Constantine), who loves gold and women above all else, investigates crime in the strange, futuristic city of Alphaville, or Nuevo York, a city entirely controlled by a computer, Alpha 60, and in which emotions are forbidden. Much of Alpha 60’s discourse is directly excerpted from the work of Argentinian poet Jorge Luis Borges, from his essays ‘A New Refutation of Time’ and ‘Forms of a Legend’, including: ‘Time is a river which carries me along. But I am time. It is a tiger, tearing me apart; but I am the tiger.’ Completing the picture is one Natasha Von Braun, played by Anna Karen, a robotic woman who ruffles Caution’s feathers with her dim sentiments and placid façade. In keeping with the noir motif, Caution saves Natasha not from an actual corporeal enemy or ‘bad guy’ but from herself, injecting love and conscious into her emotionally anaemic life.

Alphaville is bereft of authentic humanity, which makes the hardboiled scene even more potent. The film contrasts two distinctly different and strong emotional levels: there is the dark void of the computerised city, controlled, organised and docile, and the brutal, uninhibited humanity of Lemmy’s detective. One could claim Lemmy’s characterisation of unruly detective to be the ultimate representation of Alphaville’s rival. It is not enough to express human emotions, but to express them in an extreme, uncontrollable manner. Detectives fit this profile perfectly.

In the scenes where Caution appears to admire Paul Eluard’s poetry, this appears to be reminiscent of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which Smith desires all the things representative of humanity: ‘But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.’ Caution declares in a similar manner: ‘I shall fight so that failure is possible.’

Moreover the contrast between the hardboiled detective and dystopian control mirrors Winston Smith’s perceptions of humanity and rebellion in George Orwell’s 1984, where Smith favours Julie for sleeping with so many people, believing sex to be a political act against the dominating party. Sex, violence and disarray reflect the values of humanity as being in complete contrast with the mundane orderly values of Alpha 60, The Party, and controlled society in general. Anything logical is presented as starkly inhuman, as Caution yells to the master computer: ‘Fuck yourself with your logic.’ A refreshing take on the noir business in general, Godard does not stray from philosophical explorations in the midst of ‘cloak and dagger’ themes. Constantine’s Caution is an advocator of conscience and a detractor of logic. For French new wave and noir fans alike it is pure gold.